“It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data.” – Sherlock Holmes

Generally, cutting data relates to quantitative variables that determine running a cutting process numerically. Cutting data can also be referred to as cutting parameters. Cutting data consists of cutting speed, feed, depth of cut, width of cut, machining allowance (stock), number of passes and tool overhang plus additional parameters that depend on specific features of a particular machiningoperation. For example, these parameters include the spindle speed that characterizes a rotating workpiece or tool in cutting with rotational primary motion, step-over and step-down, which define a tool displacement in radial and axial directions after every pass in milling. Even though cutting data is often identified with cutting conditions, its actual value is questionable. Cutting conditions typically include machining factors that are difficult to quantify. For instance, unfavourable cutting conditions relate to a whole set of reasons, such as workpiece with skin (siliceous or slag, for example), significantly variable machining allowance that leads to changing the depth of cut, considerable impact load, due to non-uniform machined surface and surface with high abrasive inclusions.

In another case, unstable cutting conditions refer to the low stability of a complete machining system, including machine tool, workpiece holding fixture, cutting tool and workpiece, due to poor tool and workpiece holding, high tool overhang, non-rigid machine tools and thin-walled workpiece.

Principally, the terms “unfavourable” and “unstable” cutting conditions are not interchangeable. However, despite their differences in definition, these conditions are related through cause and effect and are sometimes used as synonyms in certain contexts.

In characterizing cutting conditions, the terms “heavy” and “heavyduty” machining are often used improperly. Moreover, these terms are sometimes mistakenly regarded as synonyms. In principle, “heavy machining” refers to machining large-sized and heavyweight workpieces on powerful machine tools, primarily relating to the dimensions and mass of the workpiece. In contrast, “heavy-duty” specifies a degree of tool loading and mainly characterizes a mode of machining.

A “Golden Rule” for manufacturing engineers, process planners and machinists states: “Avoid heavy-duty machining under unfavourable conditions, especially if your technological system is unstable!

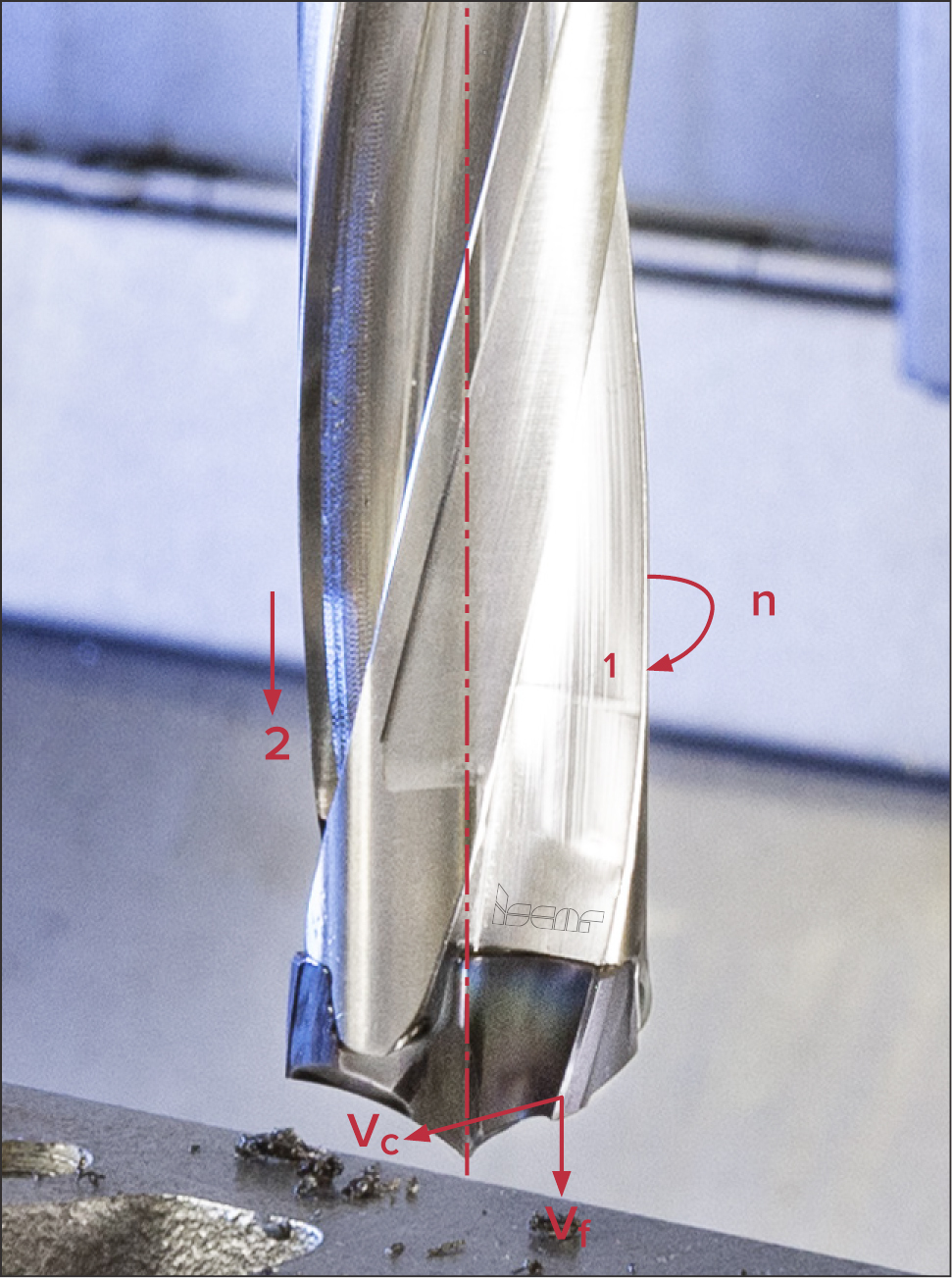

To summarize, a general description of cutting conditions depends on various aspects that are difficult to define. In many cases, finding cutting data for a specific machining operation is relied upon the user’s estimation of cutting conditions related to light, normal and hard. In primary motion, the points of a tool cutting edge move with appropriate velocities. The maximum velocity is the cutting speed vc. For example, in drilling a hole by a drill rotating with rotation velocity n, the cutting speed is the circumferential velocity of the point farthest from the drill axis. In fact, the cutting speed is the relative linear speed between the cutting tool and the machined surface of a workpiece. For a rotary body of diameter R, the circumferential velocity v is defined by the following equation:

To summarize, a general description of cutting conditions depends on various aspects that are difficult to define. In many cases, finding cutting data for a specific machining operation is relied upon the user’s estimation of cutting conditions related to light, normal and hard. In primary motion, the points of a tool cutting edge move with appropriate velocities. The maximum velocity is the cutting speed vc. For example, in drilling a hole by a drill rotating with rotation velocity n, the cutting speed is the circumferential velocity of the point farthest from the drill axis. In fact, the cutting speed is the relative linear speed between the cutting tool and the machined surface of a workpiece. For a rotary body of diameter R, the circumferential velocity v is defined by the following equation:

v=ω×R (1)

ω – angular velocity in radians per second (s-1)

In machining, rotation velocity in revolutions per minute (RPM, rpm) is used instead of angular velocity in radian per second. The cutting speed is measured in meters per minute (m/min) in metric units and surface feet per minute (SFM, sfm) in US customary and imperial systems.

vc can be calculated as below:

vc=π×d×n/1000 m/min (2a)

and vc=π×d×n/12≈ d×n/3.82 sfm (2b)

d is the diameter of a rotating tool in milling, drilling etc. or workpiece in turning that is expressed in mm in equation (2a) and in inches in equation (2b). Because both the rotating tool and the workpiece are mounted on a machine tool spindle – a part intended to transmit torque – rotation velocity n is often referred to as spindle speed.

Another velocity – feed speed vf – determines a feed motion. In fact, this is the speed at which the tool advances into the workpiece. There is a difference between feed speed and feed. The feed f is determined by the distance, which the point of a cutting edge travels along its path in the feed motion, to the appropriate number of cycles of another cutting motion. One revolution of a tool in milling or a workpiece in turning stroke in shaping – these are the examples of such a cycle. In the above case of drilling, the cycle is one revolution of a drill.

In North American countries the term “feed rate” is often used instead of the ISO definition “feed speed”. The less common term “advance” is a synonym for “feed”, like “advance per tooth” and “advance per minute” mean the same as “feed per tooth” and “feed speed”. Manufacturers can refer to “feed speed” as “table feed”. The original term refers to a classical machine, especially from previous generations, where feed motion was created by movements of the machine table.

In milling, the term “chip load” is commonly considered as a synonym for the term “feed per tooth”. This term is also more typical for the North American market. However, the correct synonym for “chip load” is “chip thickness”. In shop talk “chip load” relates usually to maximum chip thickness.

If the feed corresponds to one revolution of a tool or a workpiece, it is known as feed per revolution and designated also as f or, more rarely, fr. Feed per revolution is a common characteristic for machining processes like turning, drilling, countersinking etc.

In processes like shaping, planing and slotting, feed motion features double strokes that comprise forward (cutting) and backward (return) strokes. These processes are specified by feed per double stroke (sometimes simply feed per stroke if word “double” is omitted) fs. In many cases, however, feed per double stroke is denoted also by f.

In multi-point (multi-edge) cutting tools having teeth or flutes, feed per tooth fz is used. This is the feed that corresponds to rotation by one angular pitch of the tool teeth (flutes).

It is easily seen that:

f=fz×z (3)

where z is the number of tool teeth (flutes)

Further to this:

vf=f×n (4)

and

vf=fz×z×n (5)

Example: An ISCAR’s BAYO-T-REAM high-speed reamer carrying exchangeable eight-flute solid carbide head RM-BN9-32.000-H7LB is applied to reaming a through hole Ø32H7 mm (Ø1.2500H7) in a steel workpiece, which has a hardness value of HRC 51…53. ISCAR, as the reamer manufacturer, recommends the following initial cutting data: vc=40 m/min (131 sfm), fz=0.1 mm/tooth (.004 ipt). Find spindle speed and feed speed.

Metric system: From equations (2a) and (5)

n=1000×vc/(π /d)= 1000×40/(π /32) =398 (rpm)

vf=fz×z×n = 0.1×8×398=318.4 (mm/min)

US customary (imperial) system: From equations (2b) and (5)

n=12×vc/(π /d)= 12×131/(π /1.25)=400 (rpm)

vf=fz×z×n= 0.004×8×400=12.8 (ipt)

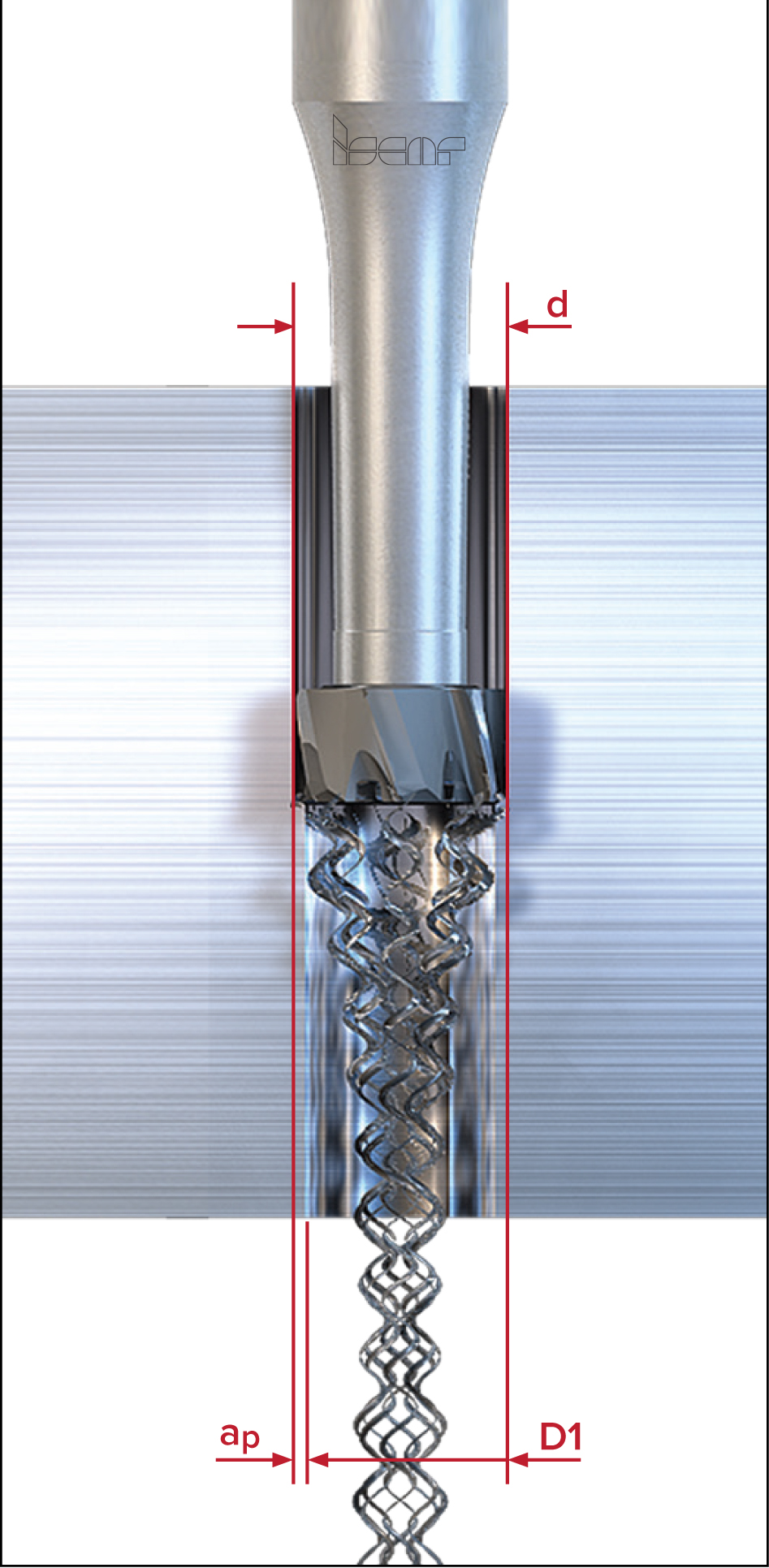

Depth of cut ap, one more cutting data parameter, is the distance between machined and unmachined surfaces of a workpiece. This distance is measured towards a normal to the machined surface. Practically, this is the distance that the cutting edge extends into the workpiece material. Depth of cut is often referred to as abbreviature DOC.

Depth of cut ap, one more cutting data parameter, is the distance between machined and unmachined surfaces of a workpiece. This distance is measured towards a normal to the machined surface. Practically, this is the distance that the cutting edge extends into the workpiece material. Depth of cut is often referred to as abbreviature DOC.

If D and D1 are diameters of machined and un-machined surfaces accordingly, ap in external longitudinal turning can be determined as below:

ap= (D1-D)/2 (6a)

In boring (internal turning), the diameter of a machined hole greater than the diameter of an un-machined hole and the previous equation takes the following form:

In boring (internal turning), the diameter of a machined hole greater than the diameter of an un-machined hole and the previous equation takes the following form:

ap= (D-D1)/2 (6b)

In parting, the depth of cut is the same as the cutting-edge width. In grooving, the depth of cut corresponds to the width of the slot, performed by the grooving tool in one pass. If the groove width is equal to the width of a tool cutting edge and the groove is generated by one pass only, the depth of cut, is the cutting edge width.

In counter-boring and reaming, the depth of cut is calculated using the following equation:

ap= (d-D1)/2 (6c)

d is the tool diameter

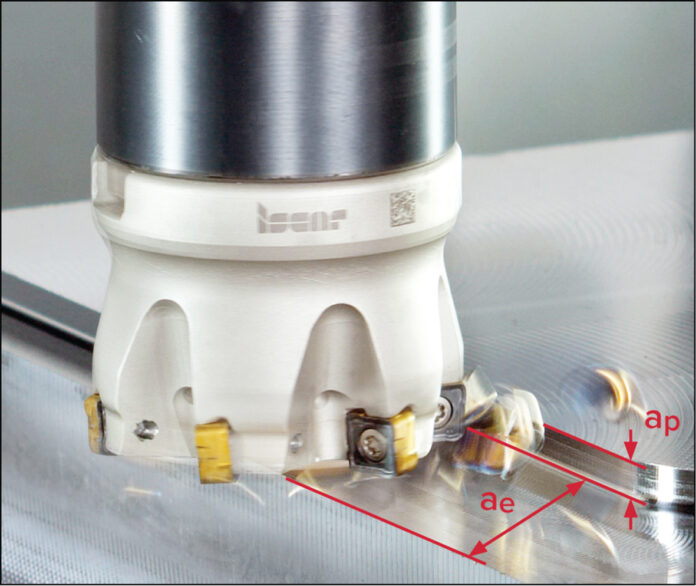

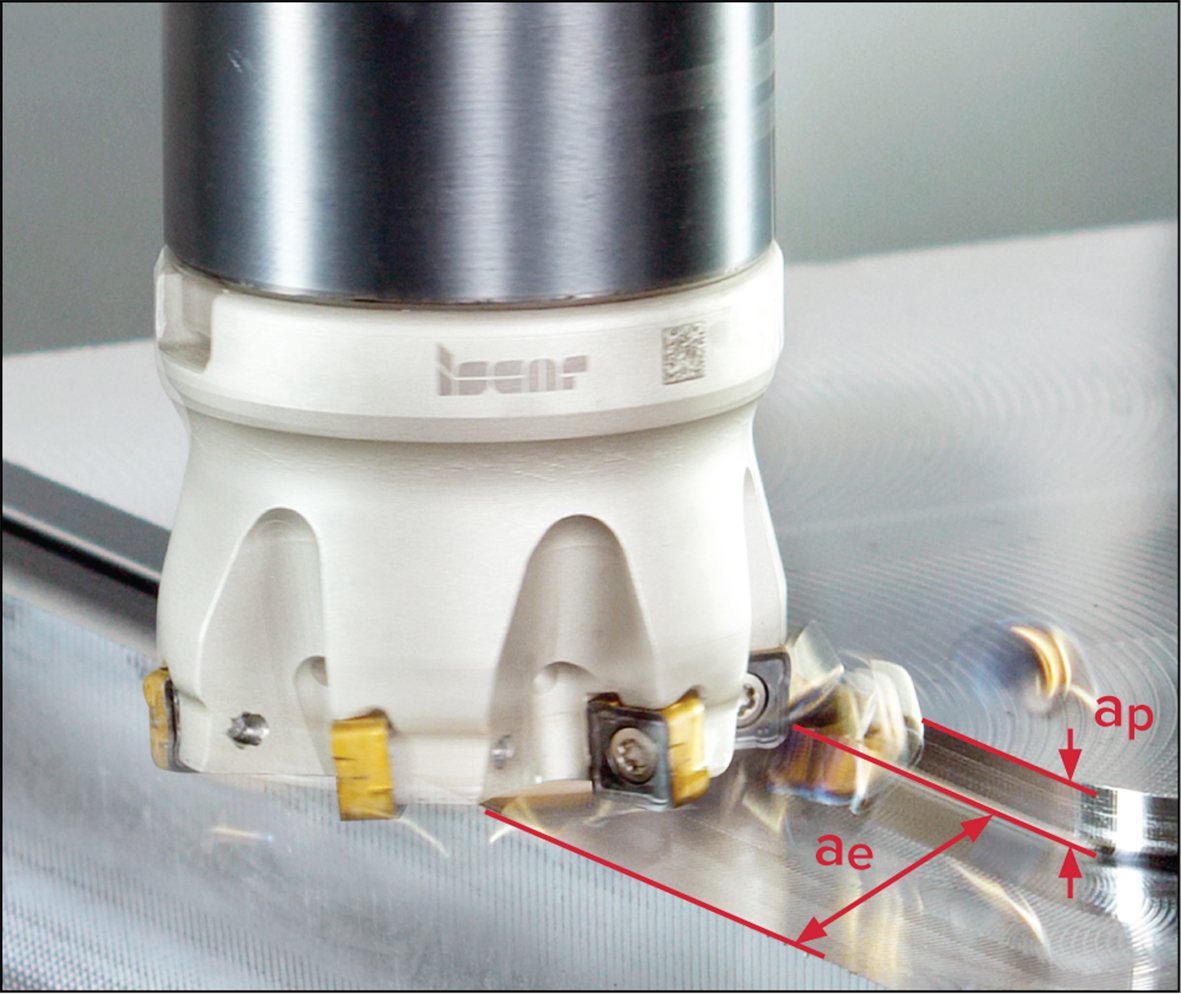

A typical milling cutter removes material with two of its surfaces at once, the periphery and the face. Therefore, in milling, the depth of cut relates to two process parameters that are measured in two different directions, such as axial depth of cut ap that is measured along the mill axis and radial depth of cut ae, which is measured radially when milling faces, shoulders and slots. The radial depth of cut is more known as width of cut – the width of a material layer that is removed by a mill in one pass.

Machining allowance, also known as machining stock or stock allowance, refers to the thickness of the material layer that should be removed during machining. There are two types of allowances, total allowance and process allowance. While the process allowance specifies the allowance for a particular machining process such as turning, milling, etc., the total allowance refers to all the material removed throughout the entire production of a part. The total allowance includes the allowances for all machining processes required in part manufacturing. Process allowance can be further divided into allowances for specific process operations, for example, rough turning, semi-finish turning and finish turning. These operations may be performed using a single tool or multiple different tools.

Machining allowance refers to the specific amount of material left for a cutting tool to remove in an application. Depending on the requirements for accuracy and surface finish, as well as possible tool limitations, like if the maximum depth of cut the tool can provide is less than the allowance, material removal can be performed with either a single tool pass or multiple passes. When defining cutting data for machining a workpiece made from a specific material on a particular machine, the following principles should be followed: In rough machining, the cutting depth is set to the largest possible value, preferably equal to the operation allowance or the greater part of it. The same approach applies to specifying the feed rate, it should be as high as possible within the constraints of existing technological limitations, such as machine power, cutting conditions, tool strength, etc.

In finish machining, the key factors for determining depths of cut and feeds are the required parameters of accuracy and surface finish, as well as the surface quality provided by the previous operation. Cutting speed depends on the characteristics of the tool and cutting material, cutting conditions, type of machining and prescribed tool life. The evolution of precise metal shaping techniques, such as precision investment casting, precision forging and 3D printing, are all capable of shaping a part very close to its final profile, significantly diminishing traditional chip-removal processes. As a result, the requirements for machining operations in engineering processes are changing. The role of productive and accurate cutting with small allowances at high speeds and feeds is expected to grow substantially, and metalworking industries will require a wider range of tools that are more precise and durable.

For more information, please contact ISCAR South Africa (PTY) LTD – Tel: 011 997 2700.